Comparative Analysis of Biocomposite Implants Vs PEEK Implants

Surgical materials have evolved to not only restore function but also integrate naturally within the body. Among these, Biocomposite screws were introduced with the aim of providing temporary support while promoting bone healing. However, ongoing research and clinical observations have shown that their degradation process, while intended to be smooth and biologically friendly, can sometimes lead to unintended challenges. In contrast, PEEK (polyetheretherketone) screws stand as bioinert guardians, offering a safer, more predictable path to recovery.

The Biocomposite Approach: Designed for Gradual Healing

Biocomposite screws, a blend of biodegradable polymers (like PLLA, PLGA or PGA ) and Bioceramics (like hydroxyapatite (HA) or Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate (beta-TCP)), were meant to be the ideal temporary scaffold. The idea was simple: they’d gradually disappear as new bone grew. However, their internal chemistry tells a different story:

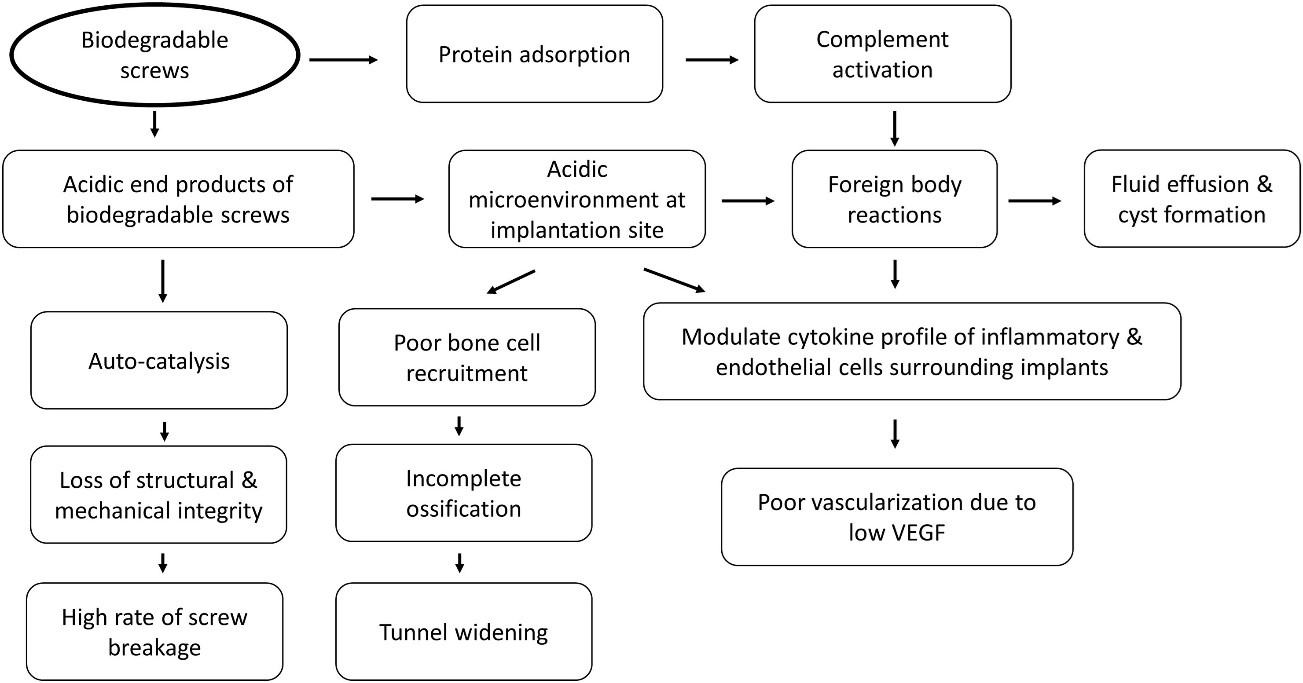

Fig I: Proposed mechanism for complications of biodegradable screws.

Behind the Breakdown: The Role of Hydrolysis

- It’s not an infection, but a fundamental chemical process called hydrolysis. In your body’s aqueous environment, water molecules relentlessly attack the ester bonds within the screw’s polymer chains.

- This is a sterile chemical reaction – no bacteria involved, just the material breaking down in a controlled, yet problematic, manner.

Byproducts of Breakdown: The Acidic Influence

- As the polymers hydrolyse, they release acidic byproducts like lactic acid and glycolic acid. This creates a localized acidic microenvironment around the screw.

- Studies: A low pH directly inhibits osteoblasts (bone-forming cells) and promotes osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells), hindering proper bone integration and contributing to osteolysis (bone loss).

- Studies: PLGA degradation products (lactic and glycolic acid) directly impair bone healing by reducing human osteoblast proliferation, accelerating differentiation, and causing mineralization failure. This chemical impact is linked to clinical failures of calcium phosphate/PLGA composites.

🔍 Sterile Reactions: A Closer Look

These acidic byproducts and non-resorbable ceramic particles act as chemical irritants, triggering a sterile inflammatory response – an alarm bell without a bacterial intruder.

- Studies: In one reported series of cases using polylactide carbonate screws, an alarming 39% of patients experienced complications such as synovitis (inflammation of the joint lining) or pretibial swelling, or both, occurring between 3 weeks and 4 months post-surgery.

- Studies: This sterile inflammation can lead to painful tibial cystic lesions and even ganglion cyst formation. One case reported a cyst forming 13 years after ACL reconstruction due to a bioabsorbable screw, highlighting the potential for prolonged irritation.

- Studies: Chronic synovitis has been observed 20 months after surgery, directly linked to the fragmentation of a PLLA femoral screw.

Previously Published Studies on Pretibial and/or Tibial Cyst Formation After ACL Reconstruction

| Author & Reference | Year | n | Type of Study | Mean Follow-up | Mean Cyst Emergence Time Post-Operatively | Location of Cyst | Type of Screw |

| Chevalier R et al. | 2019 | 53 | Retrospective Case Series | 5.4 years | 4.6 years | Tibial | PLLA, Biocomposite, PGA |

| Ramsingh V et al. | 2014 | 14 | Retrospective Case Series | 12 months | 26 months | Pretibial | Biocomposite |

| Shen MX et al. | 2013 | 1 | Case Report | Undefined | 2 years | Pretibial | PLLA |

| Sprowson Ap et al. | 2012 | 7 | Prospective MRI Assessment | 10 years | Undefined | Tibial | PLLA |

| Gonzalez- Lomas G et al. | 2011 | 7 | Retrospective Case Series | 6 months | 2.5 years | Pretibial | PLC |

| Dujardin J et al. | 2008 | 1 | Case Report | 3 months | 6 months | Tibial | PLLA |

| Busfield BT et al. | 2007 | 2 | Case Report | 6 months | 27 months | Pretibial | PLLA |

| Thaunat M et al. | 2007 | 1 | Case Report | 2 months | 5 years | Tibial & Pretibial | PLLA |

| Tsuda E et al. | 2006 | 1 | Case Report | 12 months | 2 years | Pretibial | PLLA |

| Malhan K et al. | 2002 | 1 | Case Report | 3 months | 12 months | Tibial | Biocomposite |

| Martinek V et al. | 1999 | 1 | Case Report | 2 months | 8 months | Tibial & Pretibial | PDLA |

n: number of patient; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; PLLA: Poly-L-lactide; PGA: polyglycolic acid; PLC: polylactide carbonate; PDLA: Poly-DL-lactide

Unpredictable Degradation: A Lingering Presence

- The complete resorption of biocomposite screws is highly unpredictable, often taking significantly longer than anticipated, sometimes stretching beyond five years.

- Studies: An intact PLLA screw was found and removed 12 months after surgery in one instance, while another remained detectable 2.5 years after insertion. This persistent material can continue to generate inflammatory byproducts.

Mechanical Considerations

The ongoing chemical degradation weakens the screw’s structural integrity, increasing the risk of mechanical failure.

- Studies: In studies on bioabsorbable transfemoral fixation devices, 5 out of 49 implanted devices broke.

- Studies: With Biocross pins in femoral tunnels, 17% of implants fractured, and in 6% of cases, a fractured tip migrated.

- Studies: Early PGA screws were noted to have a fast resorption rate, often before tunnel healing, leading to loss of fixation, instability, and frequent reports of foreign body reaction, synovitis, and effusion.

PEEK: A Bioinert Advantage

Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) screws offer a compelling alternative, providing stability and peace of mind by completely sidestepping these destructive chemical reactions:

- No Degradation, No Byproducts:

- PEEK is a bioinert material. It does not undergo hydrolysis or significant degradation in the body’s environment.

- Result: No acidic byproducts are released, eliminating the root cause of sterile inflammatory responses.

- Chemical Stability = Biological Harmony:

- Because PEEK is chemically unreactive, it doesn’t trigger adverse biological responses like synovitis, cysts, or granulomas.

- Studies: PEEK’s elastic modulus (around 3-4 GPa) is closer to that of human cortical bone (7-30 GPa) than metallic implants, allowing for better load sharing without the chemical drawbacks of degrading materials.

- Predictable Performance, Clearer View:

- PEEK screws offer predictable, long-term mechanical stability because they don’t degrade.

- Benefit: PEEK is radiolucent, meaning it causes no artifacts on X-rays, CT scans, or MRI. This allows for crystal-clear visualization of the graft and bone healing, crucial for monitoring without implant interference.

The Takeaway Biocomposite implants continue to serve a meaningful role in orthopaedics, especially where resorbability and temporary fixation are desired. Yet, like all biomaterials, they come with a learning curve and patient-specific considerations.

PEEK offers a complementary solution—not as a replacement, but as a versatile option in cases where biological neutrality and mechanical consistency are essential.

Surgeons today are fortunate to have a spectrum of choices, and the key lies in matching the material to the clinical context for the best possible outcomes.

References

- Fay, C. M. (2011). Complications Associated With Use of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Fixation Devices. American Journal of Orthopaedics, 40(6), 305–310.

- Unusual Tibial Ganglion Cyst Formation Due to Bioabsorbable Screw 13 Years After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. (2022). Scientific Literature. Retrieved from https://scientificliterature.org/Orthopaedics/Orthopaedics-22-141.pdf

- Polyetheretherketone development in bone tissue engineering and orthopaedic surgery. (2023). PMC. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10345210/

- (PDF) Complications Related to Biocomposite Screw Fixation in ACL Reconstruction Based on Clinical Experience and Retrieval Analysis – Materiale Plastice

- Effects of lactic acid and glycolic acid on human osteoblasts: a way to understand PLGA involvement in PLGA/calcium phosphate composite failure: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22105618/